…across Belarus, Ukraine, Israel, USA and Curacao is now on the way to your heart and to your cinema!

Click on CC (closed caption) to turn on/off English subtitles.

Trailer A Shtetl in the Caribbean from Memphis Film & Television on Vimeo.

A SHTETL IN THE CARIBBEAN tells the compelling story of two childhood friends who grew up on Curaçao, in search for their family history in Eastern Europe.

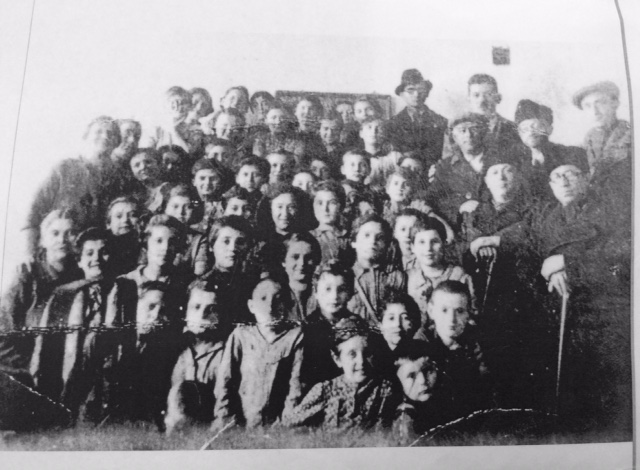

Mark and Tsale, children of Eastern European Jews that fled to Curaçao, travel back to the home countries of their ancestors. In a documentary road-movie across Curaçao, the United States, Belarus, Ukraine and Israel, we witness their discoveries, courage and despair while they are reminded of the sacrifices their parents had to make to provide their family with a better future.

This unknown story is revealed in a journey from the desolate wastelands of Eastern Europe to the exotic Caribbean, a contrast metaphoric for the history of Mark and Tsale’s ancestors.

A SHTETL IN THE CARIBBEAN originated from a strong emotion: we are all part of the same family, no matter how different we are. The film is also an homage to Curaçao, a small island with a big heart, and a place that has been a safe haven for strangers. Only in such a place a human being can truly build a home.

BIOGRAPHY MARK WIZNITZER

Named after his two deceased grandfathers per Jewish tradition, Mark Leon Wiznitzer was born in the US and brought to Curacao as a baby. There he was called “ Buchi, ” a popular island nickname that legend dates back to the strongest African slave broken by the loss of his beloved wife, and is still often given to a native first son. In Willemstad, Mark attended the Dutch-language Hendrikschool before he moved to New York City at the age of eleven with his mother. But he returned to spend all his school vacations on Curacao, where he worked with his father in La Confianza, the family-owned department store. After studying political science at the State University of NY in Buffalo, Mark went on to complete a Masters in Foreign Service at Georgetown University. He worked in Curacao for Wiznitzer Brothers, the family’s retail and wholesale business, for a year before he was selected to join the US Department of State as a career diplomat in 1976, at which time he left Curacao for good. During his various assignments in Washington DC, Latin America and Europe, he earned awards for his performance in political and politico-military affairs, and strategic trade. After retiring in 1999, Mark completed an Executive MBA in Vienna. He was a volunteer for Barak Obama’s campaigns for the Democratic nomination and election as President. As a result of his first visit in 2010 to Vashkivtsi, Ukraine, the birthplace of the four Wiznitzer brothers, he organized his family’s restoration of the neglected Jewish cemetery there. He currently lives with his wife, Paula Goddard, in Virginia, where he recently became a volunteer advocate for senior residents of Arlington County.

BIOGRAPHY TSALE KIRZNER

Tsale Kirzner was born on Curaçao as the oldest son of Socher Kirzner and Fania Shusterman, refugees who built a home on the Caribbean island in 1948. He was named after his grandfather from his mothers side, Bezalel, who was killed by a firing squad in Mikasjevits in Belarus, as a warning to the Jewish people living in the town. Tsale went to the Hendrikschool and the Radulphus College on Curaçao, after which he moved to the US to study Sinology at Harvard University and economics at The George Washington University, graduating cum laude. Since 1974 Tsale lives in The Netherlands. Tsale is married to professor Lorraine Uhlaner and is father to five children.

Read more at: http://www.memphisfilmtv.com/een-sjtetl-in-de-cariben/?lang=en