We first arrived in town on 22 October 2011 on our way by car from Kamianets-Podilskyi (Ukraine) to Soroca (Moldova), towns from which came my maternal great-grandmother (SARFAS/CHARFAS) and grandmother (BLEKHER/BLAKER/BLECHER).

This was my first visit to these regions. Our intent was to see the neighborhoods, cemetery, and sites of Mohyliv-Podilskyy, form whence came my maternal grandfather (BROWNSTEIN/BRUNSHTEYN/BRUNSTEIN), and possibly learn the location of the photography studio in town (named, “Studio F. A. Zhulyber”) where two photos were taken of him circa 1905 and 1910, before the family emigrated to America (Chicago and later, Los Angeles). The photographs show the studio name but no address in Mohyliv-Podilskyy. (In contrast, I have another BRUNSHTEYN photo taken about 1904 in Odessa, which does include a studio address, and on a recent visit to this marvelous City, I was able to kind the building where the studio had been located). I have attached these two photos, and the backside of one showing the studio information.

We departed from Lviv the day prior, where my husband and I have been living on and off for about 5 months. We were accompanied on this trip by fellow Lviv researcher (and friend) Alex Denysenko and his driver Vitaly. Both speak Russian, Ukrainian, and English, as well as some Romanian. We have traveled several times with Alex and Vitaly to Rohatyn (Ivano Frankvsk oblast) for research for my Rohatyn google research group and Gesher Galicia; we feel very comfortable with both men. Alex is a tremendous source of historical information on pre-War Jewish life and towns in today’s Ukraine.After eating a Georgian lunch at a local cafe named David’s Bar, we walked a few blocks to explore. We later learned that we were in the neighborhood known as Stare Mohyliv (“Old Moghilev”); many buildings dated from the late 19th to early 20th century.

We found ourselves standing in front of one of these lovely old buildings. It turned out to be the local historical museum, and although dark and closed, by chance the daughter of the Director walked by. She telephoned her mother who almost immediately appeared at the Museum door and opened up for us. The Director’s (mother’s) name was Luba Melnick.

We were invited in, and although the Museum is not Jewish-specific and has no Jewish artifacts on display, Luba opened a lower drawer to an armoire of books and pulled out a couple of Hebrew bibles. At least one of these bibles had handwritten notes inside, possibly in Romanian. We shot several photos of these pages.

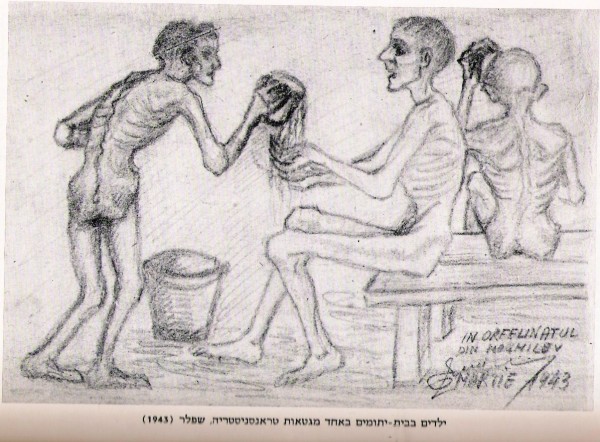

July 9 1943, Moghilău, Request

Mr. Dr. Stern I beg you to please release to me to be given at least a shirt a pair of pants a jacket and pair of [gummy shoes?].

As I am evacuated from Bessarabia from Edinizi Community we came naked as you see this am I.

Sincerely Cristina Chisilese Sioma

Luba was very friendly and pleased to answer all our questions, as best she could. She recognized the name of the photographer “F. A. Zhulyber” as it was a fairly prominent studio in town in the early 20th century, and although she had no address information or memorabilia, said it was most likely located on the main street running through Mohyliv-Podilskyy. Luba and Alex spoke at length and exchanged email and contact information; she then suggested we walk a few doors down and across the street to building #7 which currently houses the Museum of the Shoah for Mohyliv-Podilskyy.

I was surprised to learn that there are some elderly Jews still living in town; and there is one active synagogue where today they regularly meet to pray. None apparently read Hebrew, and prayers are only in Russian, discussed more below.

Unfortunately, the hours of the Shoah museum proved limited and it had already closed for the day, but we saw it would be open for an hour the following, so agreed to return. Alex acted as translator during our visit with Luba. I have promised to email Luba with information on the newly-formed Mohyliv-Podilskyy shtelink group, as well as information on Jewishgen. Before returning to our car to proceed to the Jewish cemetery in town, Alex walked into the jewelry store next door to the Shoah museum. The owner offered to call his friend, a Jewish man who might know something about my BRUNSHTEYN family (or know someone who would). Five minutes later this man arrived; meanwhile, other workers and family members of the jeweler emerged from back rooms to amusingly listen. Although this local Jewish man had heard the name BRUNSHTEYN before – and added that there had been many of that surname in town – he had no specific information for my family; he suggested we plan to come back to town the following day to meet the head of the Jewish Community (who is also the Director of the Shoah Museum) Leonid Shmulevitch Brechman. He made a phone call and this was arranged for 3:00 p.m.

From there, we drove to the Jewish cemetery. Although there had at one time been several Jewish cemeteries in Mohyliv-Podilskyy, this is the only one that survives today. The others were destroyed during WWII and the headstones destroyed or removed by the Nazis for paving roads in town (similar to the recovery project I have undertaken in Rohatyn (Galicia, Ukraine) for the paternal side of my family). Some of these headstones have supposedly over the years been moved to this jewish cemetery. The cemetery is approximately 17 hectares and is located on a hill, adjacent to Christian cemeteries, at the north-east end of town.

I was surprised not only as to its size, but to the number of headstones still standing that I could see from the road as we approached. Historical information and references on this cemetery can be found on the website for the International Jewish Cemetery Project:

http://www.iajgsjewishcemeteryproject.org/ukraine/mogilev-podolsk.html

I could also see that the headstones had numbers painted on them, suggesting that perhaps they were recorded and/or databased by someone – but whom?

We could see no cemetery office. Not could we see a formal gate or entrance. Nonetheless, we picked our way through a small entrance at the road for a Christian cemetery and finally found ourselves in a wide sloping expanse filled with Jewish headstones.

All that were still readable were in Hebrew and/or Russian. Some appeared to have fresh paint on them to make reading of the script easier. Compared to Rohatyn (where virtually no headstones remain standing), this was impressive. As far as the eye could see were Jewish headstones, several with black and white porcelain photos still visible. There was also great variation in sizes and designs. Some of the more contemporary headstones were like their Ukrainian contemporary counterparts with 3D etched images of the deceased.

The grounds were quite well-kept. The further we walked to toward the outermost edges, however, the headstones got harder to read and the grounds more overgrown. Many headstones were no longer standing. Some of the furthermost edges were almost inaccessible because of the shrubs and overgrown foliage. (I would add that there were no parts of this cemetery that were as inaccessible, overgrown, and dilapidated as we have seen in Rohatyn and elsewhere in Galicia).

We were also surprised to find a very large, sprawling section of the cemetery with German language script on the headstones. All of these headstones dated from the period of the Jewish ghetto, 1941-44.

As it turns out, these were all Jews moved to Mohyliv-Podilskyy from Romanian, Bukovina and transcarpathian towns, including many from the towns of Czernowitz and Radautz. We learned the next day from Mr. Brechman that these Jews all died in the ghetto of Mohyliv-Podilskyy during the War, mostly from disease, starvation, and neglect, and the headstones were erected by other ghetto inhabitants and family of the deceased. As previously mentioned, every headstone we saw (or nearly so), whether readable and standing, or not, had a number painted on it. Alex and my husband Jay looked around for any with the name BRUNSHTEYN (in cyrillic of course) but found none. The task was too daunting. This is a BIG cemetery. By now, the sun was setting and the wind picking up, so we decided to proceed on by car to Soroca, to return the following day.

We crossed the Moldovan border to Ukraine and arrived back in Mohyliv-Podilskyy on 23 October around 2:15 p.m. We ate a quick lunch again at the David Cafe and then went into the Museum of the Shoah. Upon entering, I was surprised to see about 12-15 elderly Jews (men and woman) sitting around a long table covered with photographs, books, and Russian and Hebrew newspapers. They were expecting us, it seemed. Mr. Brechman was at the head.

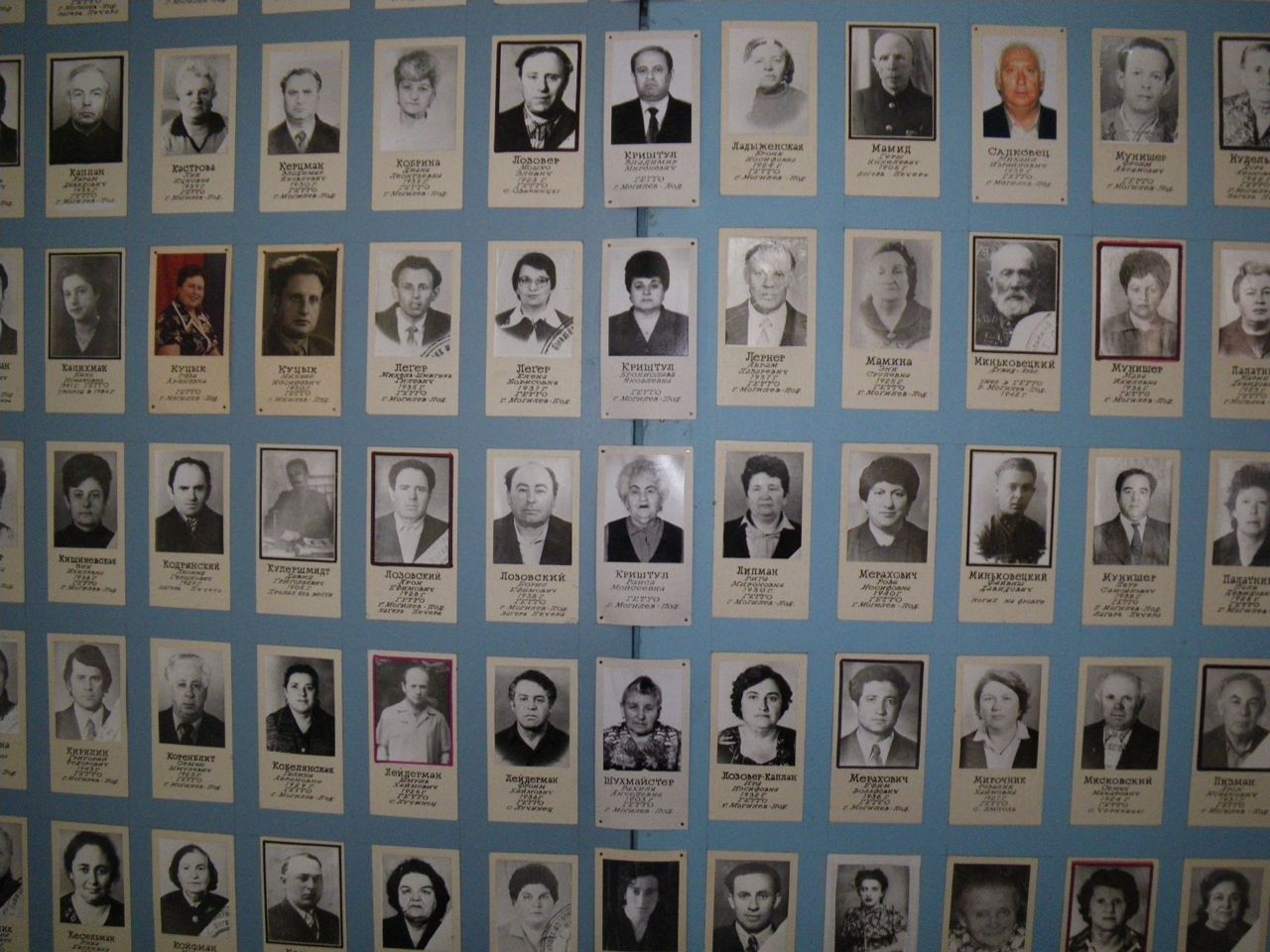

Alex explained who we were. I showed around some photos of my BRUNSHTEYN family before they emigrated in 1914 to America. One woman explained that she had family in Chicago today. Several people chimed in that there used to be many families in town with the name BRUNSHTEYN, and a few pointed to the large wall facing the front entrance – on it were a hundred or more black and white profile photos with information information about the individuals (again, all in cyrillic). These photos represented the victims of the Shoah in the Mohyliv-Podilskyy ghetto between 1941 and 1944.

Three of the photos were of people whose surnames were BRUNSHTEYN.

Mr. Brechman then allowed us to examine and photograph a bound book containing the names and information of those buried at the cemetery. This book, which was a combination of typed and hand-written Russian script, was in two parts: the first section, containing about 120 pages, was nearly complete with surnames and given names, birth and death dates, and grave location at the cemetery (section, row, and grave). Each entry was assigned a number – I assume this number corresponds to the pained numbers we saw on each headstone. Although not alphabetical, surnames were grouped by first letter (again, in cyrillic). We were able to shoot photos of about 80% of this first section, which contained about 8 or 10 BRUNSHTEYNs.

The second section was maybe about 60 pages, but most of these pages were blank except for the assigned number, thus suggesting that perhaps even grave spots missing headstones (or with illegible headstones) were also assigned numbers. A few pages had incomplete entries. We found one BRUNSHTEYN listed in this incomplete section. We were able to approxinately 5% of the second section.

A little now about this Museum. While Jay was photographing the cemetery book, Mr. Brechman gave me and Alex a tour. The Museum has three “public” rooms containing photos, maps, posters, books, newspapers, etc. about the Shoah – it is NOT limited to the Shoah in just Mohyliv-Podilskyy or Ukraine.

I also noticed quite a few books in a glass case written in French, and as I speak and read French, could see the name of the author: Madeleine KAHN. She currently lives in the 16th arrondissement in Paris and continues to write and lecture in that country on the Shoah. She has also co-authored a couple of books with Serge KLARSFELD. According to Mr. Brechman, Ms. KAHN was originally from Mohyliv-Podilskyy, although I have not been able to verify this on the internet. As a baby, she was, with her family, certainly in the area of Mohyliv-Podilskyy and spent time in various ghettos nearby where most of her family perished.

There is also a large original 1943 Romanian map on the wall of the second “public” room showing the location of various Shoah-related events and places in and around Mohyliv-Podilskyy, as well as map of the layout of the Mohyliv-Podilskyy jewish cemetery located on the wall of the third (back) “public” room.

I would also add that the Museum provides “humanitarian” services (delivery of meals, for example) to the elderly Jewish population remaining in Mohyliv-Podilskyy; they may also do this for elderly non-Jews as well in the community, but I could not say for sure. The Museum apparently receives some financial support from a Polish Catholic organization. When we later visited the synagogue in Mohyliv-Podilskyy, discussed below, Mr. Brechman directed our attention to a couple of documents on the wall, one of which – in cyrillic – made mention of such an organization in Krakow. We made a cash donation of 400 hryvnas to the Museum, or approximately $50. Mr. Bechman then invited us to see the synagogue.

For this, he joined us in Vitaly’s van along with another man who had been at the Museum with us. En route, we stopped for Mr. Bechman and this other man to greet two young men dressed in traditional attire holding torahs and others papers. It turns out that both these young men (in their early 20s) spoke perfect English because one was from Sheffield, England (his name is Yaakov Shmuel) and the other from Los Angeles (sorry, I did not catch his name). You can find Yaakov on Facebook! It seems that both men are graduates of the Rabbinical College of America, one of the largest Chabad Lubavitch Chasidic Yeshivas in the world, and located in Morristown, New Jersey. They are apparently in Mohyliv-Podilskyy for 3 weeks. Mr. Brechman then gave us a tour of the small synagogue, located in a former private residence which was recently restored to the Jewish community of Mohyliv-Podilskyy. Before the War, Mohyliv-Podilskyy apparently had about 18 synagogues; after the War, the few Jews who remained began informally but clandestinely meeting in this private home (recall that, under post-War Soviet occupation, all religion was suppressed). The Jewish community eventually petitioned the local government for this building to be recognized as a Jewish house of prayer and returned to the community as such. The original, official document granting this property is framed on the wall.

The residence is small, but contains a prayer room where the torahs are kept and furnished with chairs, desks, and bibles,

as well as a well-equipped kitchen where the meals they make and deliver to elderly people are prepared. There was a new bottle of vodka and small cookies laid out for that evening’s yortsayt commemoration.

The small tiled patio off the kitchen had had a sukkot until the day prior, when it was dismantled at the end of the holiday.

We left Mohyliv-Podilskyy at about 5:00 p.m. to return to Lviv, arriving home at about 11:15 p.m.

Here is some useful information for those wishing to travel to Mohyliv-Podilskyy and/or pursue research or projects:

Contact info for:

Alex Denysenko: tuagtuag@gmail.com

Luba Melnick: MLV-76@mail.ru

Leonid Brechman: obschina1989@mail.ru

phones: (04337) 6-57-65, 6-32-35, 6-25-02, 6-29-31

Other links of interest:

http://www.shtetlinks.jewishgen.org/sadgura/spitzer/fuhrman2.html

http://hauster.blogspot.com/2010/12/mohyliv-podilskyi-ghetto.html

http://www.jewishheritage.org.ua/en/1672/jewish-cemeteries.html

http://www.judaica-europeana.eu/

http://voices.iit.edu/

http://moldovaimpressions.blogspot.com/

http://www.bloodandfrogs.com/2011/04/jewish-gravestone-symbols.html

http://blogs.fco.gov.uk/roller/turnerenglish/

http://www.klarsfeldfoundation.org/

http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Ukraine

Here is the link to photos we have posted from our visit to Mohyliv-Podilskyy:

http://www.pbase.com/nuthatch/111023_ua_mogpod

Any of these photos can be enlarged (and then downloaded) by clicking on the individual thumbnail.Anyone wanting to do so is welcome to use and share these photos.These not represent all the photos we took, so I will also prepare a DVD of high-res (unshrunken) images for Joan FORMAN, founder of the newly-formed Mohyliv-Podilskyy shtetlinks group:

http://www.shtetlinks.jewishgen.org/mohyliv_podilskyy/

as well as Brooke Scheirer GANZ of Gesher Galicia and Jewishgen, who is interested in getting MP’s cemetery list added to JOWBR (Worldwide Jewish Burial Registry database).

Warm regards,Marla Raucher Osbornosborn@nuthatch.org